Crossing the River Twice

Did you know that at the Lord’s Supper, Jesus gave his disciples “banana bread” and “beer”?

If someone in America said you were “soft in the head,” you’d think they were insulting you. However, in Central Africa they are giving you a compliment because of your ability to learn things quickly.

If you “shiver in your liver” you might think you need a blood transfusion. Among the Uduk people of the Sudan however, “to shiver in your liver” means “to worry.” Likewise, if “my stomach sits with you” it doesn’t mean that I need to hit the gym. That’s how the aboriginal people of Australia say, “I believe you.”

Human communication is amazingly complex, and there are enormous challenges involved with translating messages from one language to another. Thanks to a generous grant from WELS Multi-Language Publications, 24 people from 8 countries visited the campus of the Lutheran Seminary in Lusaka, Zambia for the first ever Translation Seminar held in Africa. Our presenter was Dr. Ernst R. Wendland, who has served as a WELS missionary in Zambia for half a century. He has been involved with several Bible translation projects in Africa including “Buku Loyera,” the newest Chichewa translation. The workshop participants have various degrees of experience in translating books and tracts. It was our goal to give them tools to produce better translations of Christian literature from English into their local languages, so that their countrymen might have an even greater understanding of God’s love.

Translating is a very difficult task. The English word “translate” comes from a Latin word that means, “carried across.” The work of a translator is to carry a message across the divide of culture and language. However, it has been said that a translator must “cross the river twice.” In other words, it’s not enough to just choose a word or a phrase, you also have to explain what you mean. For example, the first missionaries to Africa had to find a word in the local languages for “God.” Often they chose the name of the god of the local religion who was the creator, father, or highest of the gods. Then they had to explain the difference between the pagan god and the God who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

A translator must not translate from one language to another in a literalistic way. For example, in Matthew 5:2 the Greek says that Jesus, “opened his mouth and taught.” Some readers might ask, “Why did Jesus open his mouth? Was he yawning because he was tired?” A famous hymn says that “Christ is the way, and Christ the path,” but Jesus did not come here to build literal roads. A missionary to India illustrated the concept of “standing on the Word of God” by putting his Bible on the ground and stepping on top of it. In the eyes of the people of that culture he was showing great disrespect to the Bible, and it caused an offense that took years to overcome.

There’s an Italian phrase, “traduttore, traditore” which means “translator, traitor.” A translation must not be literalistic in its form, but it must be faithful to the original content. Sometimes that means that translators must be creative. How do you translate, “I am the Good Shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me” (John 10:14) into the language of people who do not raise sheep? What word do you use for Noah’s “ark” in the language of a people who live in a landlocked country and do not use boats? Christian translators have long debated among themselves how to translate the word “God” into Arabic, because there is no other word to use other than “Allah.”

“Behemoth” (Job 40:19) is a Hebrew word that literally means, “large animal.” If we are translating for an African audience and use their word for “hippopotamus,” is it a faithful translation? The Bible often uses the phrase, “white as snow” but there is no word for “snow” in many African tongues. Some translations say, “very white,” “white as a bird,” “white as flour,” or “white as fog.”

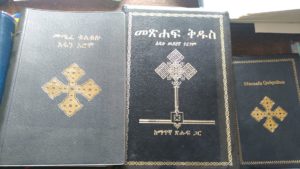

In the account of the Last Supper, the translators of the first Chichewa Bible chose to translate the word “bread” with the word “mkate,” which originally was a flat cake made from plantains. Grapes do not grow in Central Africa, so there is no local word for “wine.” The Chichewa word “mowa” means fermented drink made from grain (beer). Are you beginning to understand the challenges that face translators?

And do you understand how important it is to get it right when translating, especially when working in a culture that is hostile to the Gospel. The Koran says that Allah has no family, so to say “Isa bin Allah” (Jesus Son of God) is blasphemy. Some Arabic translations of the Bible use the phrase “Jesus beloved of God,” although this can also be misunderstood.

Christian translators must not only know the languages they are working with, they must also understand the doctrine of the Bible. The phrase, “keep the unity of the Spirit” (Eph. 4:3) could mean, “unity created by the [Holy] Spirit,” or “[Christian] spiritual unity,” or even “the Spirit’s unity.” It most certainly does not mean, “unite the [ancestral] spirits,” which is how a literal translation of that phrase is understood in Swahili.

“Faith comes from hearing the message, and the message is heard through the word of Christ.” (Romans 10:17) God communicates to us through the Bible, which is written in human languages. If it is so important to understand God’s Word accurately, why did God mix up the world’s languages at Babel? Here is a partial answer, proposed by Dr. Wendland at the Translation Workshop and one that I can verify from personal experience: when you translate from one language to another, you are forced to work harder at understanding what the text is saying.

The Amharic (Ethiopia) word “atereguwagom” (meaning: “translate”) literally means, “to break into pieces.” Translating forces you to break down a text into its most basic meaning before you can reconstruct it in another tongue. Language is God’s gift to the human race, and each language has its own “genius,” i.e., its own unique way of describing reality. Its only fitting that the infinite Creator of the cosmos would give finite human beings a multiplicity of ways to communicate the multi-faceted beauty of his love.

Missionary John Roebke lives in Malawi and serves as the Communications Director for One Africa Team

Learn more about the work of WELS Multi-Language Publications at www.wels.net/mlp